Blindsided

Building a startup in the music industry is a fairly reliable guarantee that you’ll run into people behaving in ways that you can’t explain. Often, this behaviour will actively, or through sheer apathy, work to undermine your objectives.

Incentives are often the culprit, specifically misaligned incentives. Simply, your goals are not the same goals as the people whose assistance you require—which is clearly unlikely to produce good outcomes.

Founders are often confused because they assume that everyone in music is on the same side, the side of music, the side of art and artists, right? But, time and time again, experience proves otherwise. In this essay, I hope to shed some light on the system that produces these incentives. While I was building my own blockchain music startup (this was before the web3 rebrand), a chance encounter gave me a window into a phenomenon called juice.

WTF is Juice?

Juice was revealed to me by a seasoned music executive at the end of a lunch meeting as they breezily forecasted the demise of my startup. Their theory was simple: Juice was the precursor to momentum and, ultimately, success in the music industry and we had none. The delivery was even simpler: "You got no juice".

On the face of it, this wasn't too surprising.

We'd known for months that we were losing the interest of labels, publishers, and performing rights organisations—we could feel it. The juice I assumed he meant, like "executive buy-in" or "influence", was waning. Speculative interest in crypto, which was subsidising our development efforts, was slowing and would soon snowball into the crippling winter hibernation of 2018. Plus, we'd been through so many rounds of stakeholder-appeasing mollification, failed launches, and ideological back-tracking as to render our USP a mere p at best.

But this was not juice. At least not quite the juice the exec spoke of. For them, Juice was tangible. It was the crucible into which they and their peers were born and the altar on which they were sacrificed. And we were unwitting participants in their juice game.

But a comprehensive understanding of juice, requires a basic understanding of the system that creates it—A&R.

A&R or Artist and Repertoire, for anyone that isn't familiar, is the process by which labels deploy capital to acquire IP and subsequently maximise its value. Broadly speaking, this includes: finding artists, assessing their quality, securing contracts with artists over-and-above competitors, and navigating the web of personal relationships and specialised knowledge required to maximise and extract value from anything created by that artist during the length of their contract.

This process, signing talent, is the primary concern of what we commonly refer to as the "music industry". It is the engine that both urges the locomotive forward and creates the incentives that dictate the behaviour of the drivers, passengers, rail, stations, signals, etc. “Hiring? Oh, you mean People A&R.”, “Partnerships? Media A&R.”—licensing or investing is nothing but Startup A&R.

Importantly, when everyone at the table has a sizeable chequebook, status, not cash, delivers the most lucrative signings. Major label A&R functions as a status-game.

Juice is status transmogrified into a capital asset—earned and collected, bestowed and traded, amassed and liquidated—that spans both utility and social capital. Hence, "Got no juice" was also a commentary on those who had taken up the mantle across the industry to represent us within their respective organisations and their ability to say “yes”, get the ear of the people that could say “yes”, over-turn a decision against us, or—in simple terms—get shit done.

Once you begin thinking about the music industry as an industry predominantly driven by the manufacture and accumulation of juice to attract artists, you'll have a better framework for understanding the dynamics that determine whether or not you'll be successful as a music technology startup. Couple this with the crucible of raising venture funding and you have a fairly robust model to predict the probability of success for any music technology venture and explain the treatment of music startups by VCs.

The only real enemy of a kingmaker is another kingmaker.

If you choose to build in this space then it's useful to understand that time spent navigating major labels is ultimately a waste of you and your team's energy and resources unless you have juice. They are profit-seeking businesses that owe you nothing. Conserve your energy for battles you can fight on your own terms. Focus entirely on building products for artists, creators, fans, suppliers, users, contributors, customers and everything in-between in markets where you do not have to ask permission before you can serve them. Accumulate juice.

If you find yourself asking for it, you have failed. Only by refusing to ask, do you have a shot at actually creating juice.

And nestled deep within this insight is a defiant call-to-arms.

Obligation to disrupt

On Spotify’s Loud and Clear website, they explain that of the 8 million people that have uploaded music to Spotify:

We estimate that there are around 200,000 professional or professionally aspiring recording acts globally. […]

There are 165,000 artists who have released at least ten songs all-time (meaning they have a body of work to earn from) and average at least 10,000 monthly listeners (meaning they have been able to attract the beginning of an audience). […]

Based on these estimates, more than a quarter of these professionally aspiring artists generated more than $10,000 in payouts from Spotify alone last year (suggesting more than $40,000 in total recorded revenue, and more when you consider touring, merch, and other business lines).

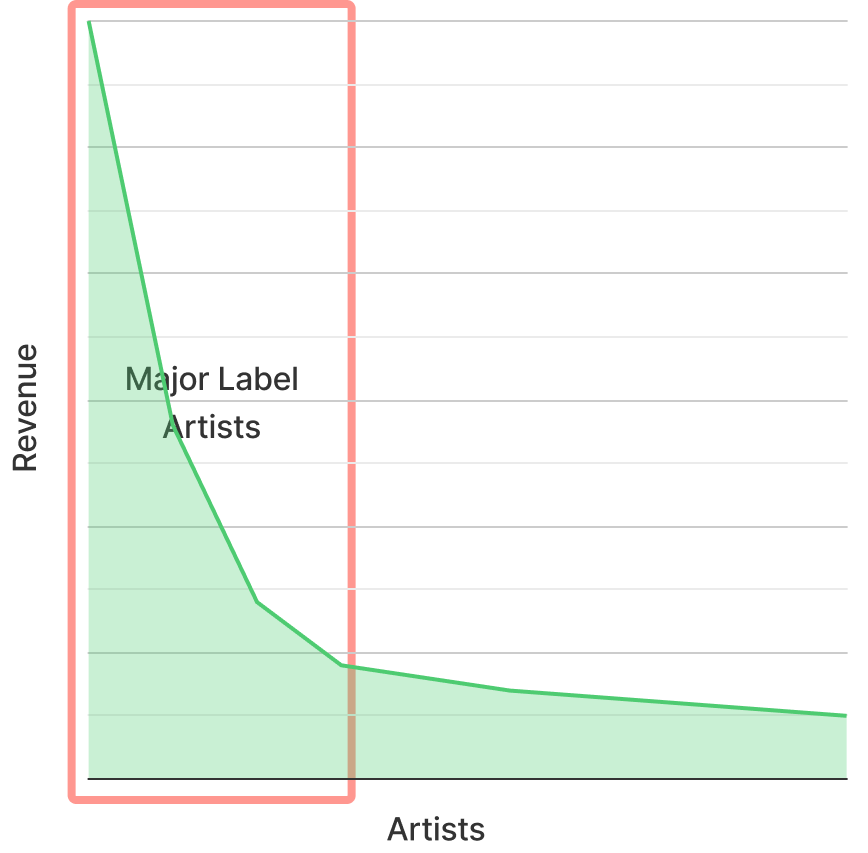

98% of artists on Spotify have released less than ten songs and/or do not average more than 10,000 monthly listeners. Regardless of how you interpret the parameters that produced this statistic, one thing is certain: the long tail is more long than tail.

The major labels are solid businesses with robust, durable business models. They endure because they put juice to work and, in doing so, provide one of the most important roles in the market (after the artists who create music, obviously 👀): investment.

The majors invest in the top 10% of IP creators in terms of value, expecting some percentage to fail and a small percentage to generate outsized returns. Successful assets join existing catalogue and continue to return royalty revenues as they generate plays, funding investment in new IP creators and the development of new catalogue.

Given the strength of their position and the energy required to maintain it, there is minimal threat from competitors (outside the Big Three) and little incentive or energy left to innovate.

Unfortunately, for new entrants, they cannot service this revenue stream directly unless they service the major labels. Neither the fans interested in consuming music in new ways nor the artists who create it.

Effectively, the major labels act as final boss gatekeepers for all music tech startups that make use of recorded music. Startups that are deemed worthy must provide payment, typically in the form of equity in their startups, in exchange for access to licenses (unless they have accumulated juice without the majors). This value exchange is in keeping with the major label model of extracting as much revenue as possible from their IP but reduces the incentive for would-be innovators to create new value in the space, minimising the talent pool, and reducing the amount of capital allocated by investors.

This conserves the existing major paradigm and is, unequivocally, counter-productive for artists, creators, and fans.

This practice also constrains the ultimate value created by artists and their work by reducing the total number of people who can identify and exploit opportunities, the range of skillsets that can be applied to the problem of finding productive uses of music, and the types of environments in which music can play a role. Here, the free market has a higher probability of finding and selecting innovations which could significantly expand the market for music but must settle for access gated by well-intentioned, risk-averse employees incentivised to limit downside over-and-above seeking upside.

However, disruption is not a matter of if but a matter of when. The music industry doesn’t exist in isolation and technological innovation marches forward undeterred. The major label paradigm unwittingly constrains innovation in music, forcing teams to play juice games when their energy should be focused on building value for customers. As technology matures, it's becoming increasingly obvious that artists and fans are better served when new entrants have complete agency to do so on their own terms.

Though a number of startups, Spotify included, have traversed the major label gauntlet and succeeded, there are a growing number of startups focused on areas of the market that are underserved or historically low-value to major labels, where a disruptive force may one day arise.

Already, there are a few bright sparks on the horizon.

This was all inspired by No Juice rap song by lil boosie

https://youtu.be/4IljoY0vhoE